The children

On April 25th 2016 I was sitting in my living room in Hamburg thinking about the two celebrations that I was missing back in my hometown: my mother’s birthday and Liberation Day. I started remembering my father’s grandmother stories about World World II, how she would live in an occupied land with my by-then toddler grandmother, and that the only two words she ever learned were “Wasser” and “Kaputt”. She also used to tell us that as a young girl she served as a housemaid in the house of Guglielmo Marconi. I started thinking about when my other grandmother showed me a box full of photos that her relatives living in Africa in the 1920s would send to the family. I started thinking about how that same grandmother divorced in the 1970s, when it was barely legal in Italy to do so. I remembered my father’s stories about his childhood in a violent, working class neighbourhood, and how people he knew sometimes got shot in the streets. I remembered when a friend of mine told me how his parents met on August 2nd 1980, in the aftermath of the terrorist attack at the Central Train Station of Bologna. I remembered stopping in the middle of the Pub when the TV started showing the first images of the Tōhoku earthquake, holding empty beer glasses and wondering if my former Japanese flatmate was okay. I thought about how I felt when I was waiting for my friend in Paris to finally tell me she was safe, and how we had been to the Bataclan together when I visited her a couple of years before. As obvious as it is, it never occurred to me before that we do not simply witness the events, but they become part of our lives. That’s why I decided to explore these stories, to find out which pieces of history we are made of.

Part I - Lella

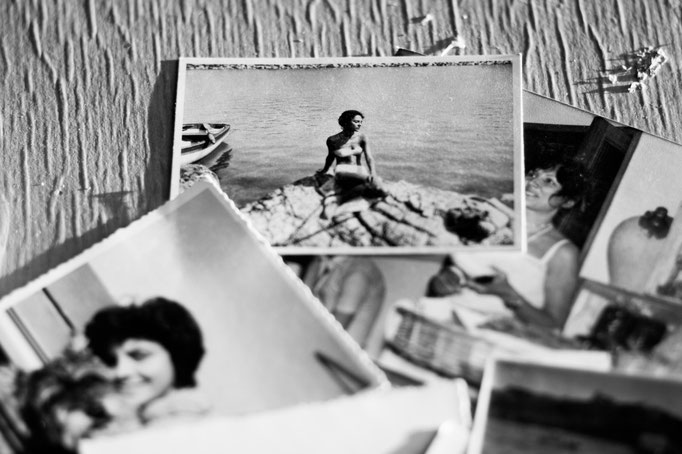

She sits, half of her body in the light of the setting sun, sawing me a crown. This room has been a bedroom, a living room, a shop. I spent countless hours in it. I spent countless hours watching my grandmother work, cook, fish, as she taught me how to do all of these things. But it’s only now, by asking her questions that I would ask a stranger, that I begin to understand her resilience, her ability to adapt to the world and to carve into it at the same time, like water.

Her name is Gabriella, but most people call her Lella most of the time. She was born in 1939 in Pisa, to a wealthy industrial family closely tied with the Fascist party. Her grandfather and his brother started working every afternoon after school when they were still children. They started out by giving passage to people across the river on a small boat. With the money they earned, they bought a small portion of land in the stone pine woods, where they could harvest pine nuts. With the money from the pine nuts they eventually built two glass factories, bought more land, and several houses. They owned so many pieces of land that during the war the family lost track of some of them.

“A few years back Massimo [her brother] and I received a letter from the city council saying that a piece of land here in town, right where they now built the supermarket, was declared abandoned and no longer belonged to us. We didn’t even know it was ours.” She said, making no mention of how peculiar it is that she’s been buying her groceries in that same supermarket every day since it opened.

Before the war, her aunt married a prominent member of the Fascist Party and together they spent the better part of the Ventennio in the African colonies. During those years Aunt Silvana used to send photographs and raw coffee beans back to Italy. My grandmother and the other children would roast the beans in the garden of the summer house in Marina di Pisa. The family would send back tailored gowns for Silvana to wear at parties. Most of the pictures I’ve seen of the Colonies have short descriptions but only a few report the exact location. Some say Tripoli, some Bengasi.

Italy officially joined World War II in 1940, and both Pisa and Livorno became a target for Allies’ aircrafts because of the presence of Italian navy and airforce military bases. The bombings gradually intensified, until my great-grandfather remained stuck in a gallery in Livorno during one. He was left unharmed, but shortly after the accident the whole family fled the city for the country side. They lived in the big house of a Earl in Montecchio.

The memories of her time in Montecchio are scattered, a recollection of sporadic episodes, just like everyone’s childhood memories.

Whenever the bomb alarm rang, her father always went down to the shelter late because he would refuse to go down unless properly dressed. In her words, “Whenever he finally arrived, we were ready to go out”.

One of the countermeasures against the bombings were silver filaments, dropped in the air in order to confuse the enemy and make it more difficult for the Allies’ aircrafts to acquire the target. At Christmas, the children picked them up from the ground where they lay and used them to decorate the tree. To this day, Christmas decorations are one of her favourite things: I remember decorating the tree with her, hanging precious looking glass decorations and then covering it all with silvery filaments.

The Allies eventually invaded Italy and, after the armistice, so did the German army. In the German-occupied areas Mussolini established a new government called the Italian Social Republic, and the resistance started a civil war against the German occupation. Bologna, my hometown, was one of the strongholds of the resistance and most of the people I grew up with had a grandfather in the resistance. My grandmother, instead, witnessed one getting executed. In truth, she doesn’t remember if the prisoner was member of the resistance an American soldier, but one morning she heard her mother screaming in the courtyard, and then a machine gun being fired.

“Two days earlier, I watched a pig getting slaughtered in the courtyard. I was terrified of the screams and the blood. When I think about the pig, I always think about the soldier as well.”

Her father fought in World War I but he never received the draft letter for the second war, probably, because nobody knew where he lived anymore. Except one day German and Italian soldiers came for him and wanted to arrest him and execute him as for desertion, but the Earl claimed that he father was one of his servants and the army couldn’t take him.

After some time in Montecchio, they had to move to Florence, where they frequently changed apartments. Besides her unintentionally deserting father, they had an actual deserter and a secret Jew (the husband of a cousin) in the family, and they had to be extra careful in the German occupied city. Towards the end of the war, when the nazi forces where retreating, they started blowing up the bridges behind them in the attempt to slow down the Allies.

“I didn’t understand what was happening, I just remember the fires on the river, and it looked beautiful.”

In late April 1945 Mussolini was captured and killed by the resistance, and the whole family grieved in secret then proceeded to get rid of any object that could identify them as Fascists. Her aunt came back from Africa to live with them after her husband died under unspecified circumstances.

After the end of the war they went back to Pisa only to find out that all of their houses had been turned into rubble by the bombings. They headed to their summer house in Marina di Pisa, the one where I spent entire summers and where I’m photographing and interviewing her. During their absence the house had been occupied by refugees and all the windows had been shattered by explosions. She hated washing her hair in the freezing room upstairs: there was no heating, no windows, and the water in the basin would often freeze in the winter. Sometimes a sea storm would wash a mine ashore and they would have to leave the house while they were disarmed. They once found a block TNT in the garden.

Approaching the first elections the family dreaded the results. What if the Communist were to win? The other kids from left wing families mocked her telling her they had a list of the Fascists they were going to be allowed to kill after the election, and her whole family was on it.

During the years of the reconstruction her father started working for the RAI (Italian Public Television and Radio) and was transferred to Bologna. The whole family followed and there my grandmother attended Art School, where she met my grandfather. My mother was born in 1965, my aunt in 1966, and my uncle in 1970. During that time she approached the macrobiotic philosophy and advocated for the legalisation of abortion and divorce. She would go to the countryside with a friend and give out pamphlets. She also discovered that my grandfather had repeatedly cheated on her, and despite years of trying to get along and keep the family together, they eventually divorced in 1975. She met her current partner through his former wife, whom he divorced after she fell in love with his cousin. They still live together, unmarried, in the family summer house in Marina di Pisa. The house still stands right in front of the sea, the two separated only by a one way street and several layers of artificial rocky shore, placed throughout the decades replace the sand that the sea level rise slowly swallowed, and to break the waves that crash sometimes all the way across the street to the front of the houses when the Libeccio storms come. But mines no longer come ashore.